The "Chemistry Table" Test: Why Smart People Fail

Merit is a myth. Here are 3 brutal truths from Bell Labs legend Richard Hamming on how to unlock your true potential.

“Just do the work, and the rest will follow.” How many times have we told ourselves that lie?

It goes like this: You lock yourself in a room. You decline the invitations. You do the deep work, writing the code, drafting the strategy, building the product. Then, you emerge, blinking in the sunlight, expecting to find the world waiting to applaud.

We want to believe that merit is a magnet. We want to believe that if we just work hard enough, visibility will take care of itself. That if the work is good, the audience is guaranteed.

But that is a fantasy.

That illusion was shattered for me when I read a transcript of a talk given in 1986 by Richard Hamming. Hamming was a titan at Bell Labs, a man who worked alongside the fathers of Information Theory. Throughout his career, he was obsessed with a nagging question: Why do some capable people fulfill their promise, while others with equal talent are left wondering what they might have accomplished?

To answer this, he gave a famous talk titled “You and Your Research.”

While Hamming was speaking to scientists in white coats, his advice is actually a brutal reality check for anyone trying to reach their potential and goals in life.

Here are three uncomfortable truths Hamming revealed about what it truly takes to reach your full potential.

1. The “Chemistry Table” Test

Hamming didn’t just theorize about greatness. He investigated it. He used to eat lunch with the physicists, but when the Nobel Prize winners left, the conversation turned dull. So, he moved his tray to the “Chemistry Table” to find new ideas. He started asking the chemists a terrifying question: “What are the important problems of your field?”

After a few weeks of listening, he asked: “What important problems are you working on?”

And finally, when the answers didn’t match up, he delivered the kill shot:

“If what you are doing is not important, and if you don’t think it is going to lead to something important, why are you at Bell Labs working on it?”

He wasn’t welcomed at lunch after that.

But most of us are sitting at that Chemistry Table right now. We fill our days with ‘busy work’: endlessly refactoring code that already works, bikeshedding over variable names in code reviews, or reorganizing the Jira backlog. It feels productive, but it’s actually a defense mechanism. We pick the safe, solvable Jira tickets to avoid the terror of the complex architectural problems that actually matter.

The Rule: If you aren’t working on the one thing that could actually level up your career, you must re-evaluate your options.

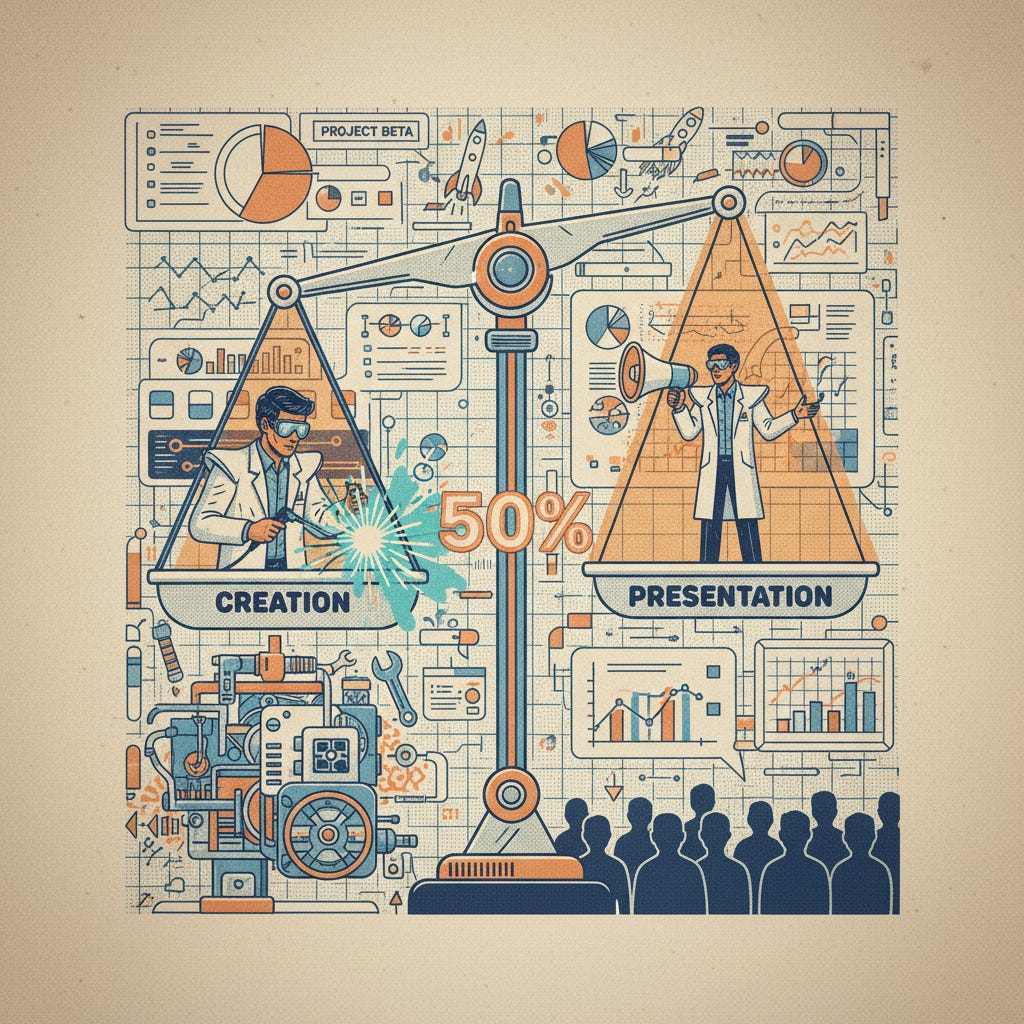

2. The 50% Rule

Your work should speak for itself, right? In fact, this is the biggest lie that we have been told. In creative and technical fields, “selling” is often underrated.

Hamming disagreed entirely. He saw brilliant people at Bell Labs who had world-changing ideas but kept their heads down. They would file a quiet report weeks after a project finished, but by then, the decisions had already been made.

He stated his rule bluntly:

“I believed, in my early days, that you should spend at least as much time in the polish and presentation as you did in the original research. Now at least 50% of the time must go for the presentation. It’s a big, big number.”

Why 50%? Because the world is noisy.

If you build a product but don’t market it, you haven’t finished the work. If you write a brilliant strategy document but don’t present it persuasively to your boss, you haven’t finished the work.

Hamming noted that if you don’t advocate for your own ideas, you aren’t being “humble.” You are crippling the impact of your work.

If you don’t promote your work, no one will do it for you!

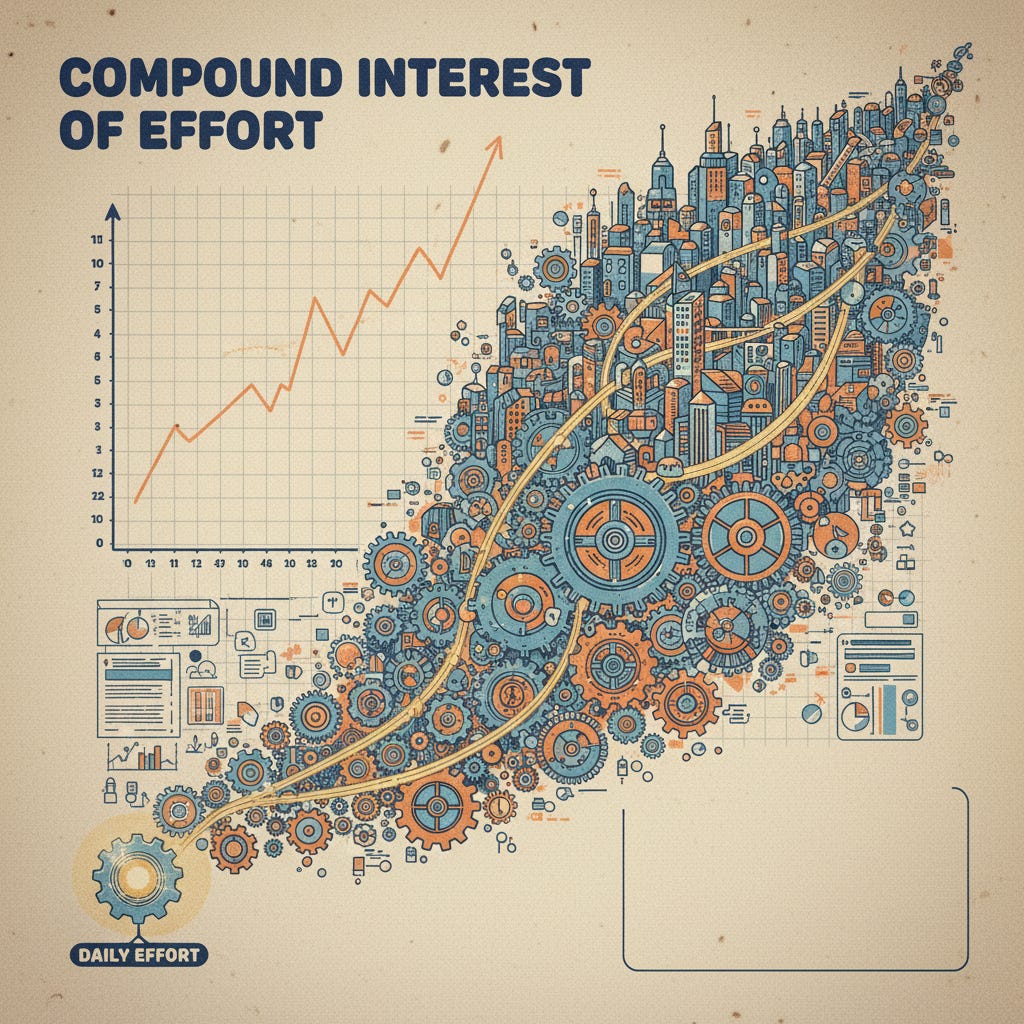

3. The Compound Interest of Effort

We often look at “geniuses,” whether it’s Elon Musk, Taylor Swift, or the star developer sitting next to you, and assume they are just smarter.

Hamming was suspicious of this. He asked his boss, Bode, how someone like their colleague John Tukey knew so much. Bode’s answer changed Hamming’s life: “Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest.”

If you have two people of roughly the same ability, and one works just 10% harder than the other, the output isn’t 10% higher. It is 2x higher over a lifetime.

“The more you know, the more you learn; the more you learn, the more you can do; the more you can do, the more the opportunity.”

This isn’t about “hustle culture” or burning out. It’s about the compound interest of focus.

Hamming realized that if he carved out just one extra hour a day for “Great Thoughts” and thinking about the future rather than just putting out fires, that effort would compound. Most of us live life linearly, doing the job and going home. Great work happens when you invest a small amount of energy today that makes you smarter tomorrow.

Luck Favors the Prepared Mind

Hamming believed that even if you follow all these rules, you face one final trap: Success itself.

Success tempts you to repeat your greatest hits until you become a dinosaur. Hamming’s advice was to force a reset: change your professional focus every now and then. You need to make yourself a beginner again (not a dramatic change) so you remember how to learn. Don’t just sit in the shade of the oak tree you already grew. You need to plant new acorns. If you write code, look at the algorithms that power it. If you’re a software engineer, pivot to AI.

Hamming’s talk is a reminder that we have more control over our careers than we think. We often attribute success to luck. But as Hamming said, quoting Pasteur: “Luck favors the prepared mind.”

You prepare your mind by asking the uncomfortable questions at the Chemistry Table.

You prepare your career by selling your work as hard as you create it.

And you prepare your soul by keeping your door open to the world.

Hamming refused to accept alibis. He didn’t believe greatness was reserved for the lucky few. He believed it was a choice you make every day. So take his final challenge to heart: “Therefore, go forth and become great!”

Here is the link to the full transcript of the source.